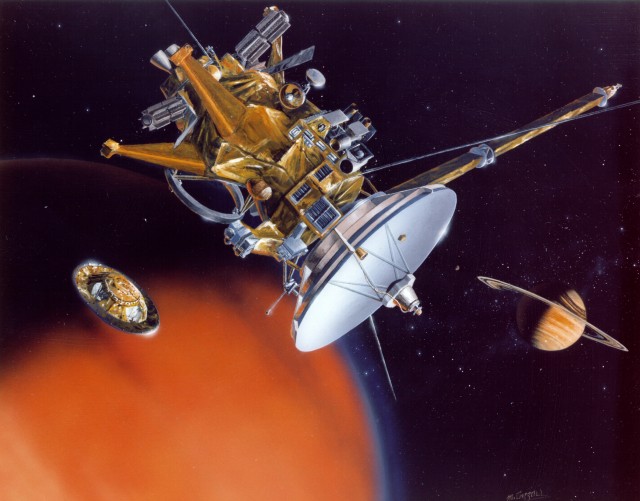

Artist's impression of a ULX, which could be either a black hole or a neutron star in this image. Coming "towards us" is the outflow of gas, moving at relativistic speed. (credit: ESA–C. Carreau)

Researchers are gaining ground in the struggle to understand the mysterious objects known as UltraLuminous X-ray sources (ULXs). These objects, named for their extreme brightness at X-ray wavelengths, are thought to be dense, compact objects like black holes or neutron stars. Their luminosity (which extends to other wavelengths) arises as they actively draw matter from an orbiting companion.

“We think these ‘ultra-luminous X-ray sources’ are somewhat special binary systems, sucking up gas at a much higher rate than an ordinary X-ray binary,” said Ciro Pinto from the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, UK, an author of a recent study. “Some host highly magnetised neutron stars, while others might conceal the long-sought-after intermediate-mass black holes, which have masses around 1000 times the mass of the Sun. But in the majority of cases, the reason for their extreme behaviour is still unclear.”

It’s been difficult to study them in detail because we've lacked the sensitivity needed to identify the emission lines and/or absorption lines created by specific elements. When light passes through material such as gas, certain wavelengths are absorbed by elements in the gas, leaving a blank line in the light source’s spectrum. Emission lines are light emitted by the element itself.