The problem with being a safety-conscious, responsible drone operator is that it's much easier to actually fly the drone than it is to comply with Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules. If we're ever going to have instant Amazon Prime Air deliveries, Domino's Pizza drones, and other flying robot helpers, complying with those rules needs to get easier—it also needs to get automated.

At the recent Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) Xponential conference in New Orleans, Amazon Prime Air Vice President Gur Kimchi outlined Amazon's vision for how that might look. Kimchi and Amazon propose an approach that uses "federated" traffic control—the sharing of information between air traffic control systems, operators, and drones themselves to enable a safer yet more crowded sky. The groundwork for such a system is already being laid—in part thanks to software developed by a Santa Monica, California, company called AirMap.

AirMap has released an application for Apple iOS that could make drone operations safer by directly connecting drone operators to airport operators and air traffic controllers. The app is built atop an Internet application interface that is also being used by drone manufacturers like DJI, 3D Robotics, Yuneec, and the commercial and military small UAS manufacturer Aeryon Labs. This setup allows users to integrate the same services directly into the software used to fly drones.

AirMap has already brought 75 airports onboard with the application, which gives airport managers a "dashboard" from which they can grant or withhold permission to fly and set specific automated policies for certain areas near their airports. Eventually, the software will let drone operators see each other as well as data about crewed aircraft on courses that might conflict.

The drone phone tree

Today, if you want to fly a drone in compliance with FAA rules, it's relatively easy—that is, as long as you're flying far from civilization, in visual line of sight, below controlled airspace, and nowhere above people or cars. Fly one anywhere else, and things get complicated.

Odds are that there's an FAA-designated airfield near you, whether it's an actual airport or the helipad at a local hospital. "In 2012," explained AirMap CEO and co-founder Ben Marcus, "congress passed a law—Section 336 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act—which requires recreational operators of drones to give notice to airports and air traffic control when flying within five miles of an airport. So to give notice, you would pick up a telephone or knock on the airport manager's door and say, 'Hey, I'm going to fly over the 7-Eleven down the street.'"

Technically, the regulations apply even if you're flying a kite. (By the way, if you're flying your kite more than 150 feet up without proper lighting, this is also an FAA rule violation). At the park near my house, that means contacting 10 different entities—seven hospitals, a city water filtration plant, city police headquarters, and a hotel that occasionally allows helicopters to land on the roof of its parking garage. I know this mostly because of an "app" released by the FAA earlier this year called B4UFLY, intended to help drone owners become aware of things like temporary flight restrictions and the restricted airspace near airports. But B4UFLY doesn’t provide any way for would-be drone pilots to reach airports to get permission (not even phone numbers). All the app gives is a latitude and longitude for the location of the airports nearby.

The current system of contacting airports also ignores another important part of drone safety. While the FAA's air traffic control system may eventually provide data to other organizations, "in the interim there's a whole lot of other public safety entities that have an interest in drone safety," Marcus explained. He's not just referring to airports, but local police and other organizations need to be aware of what's in the air, who's flying it, and where it's flying. Currently there's also no easy way for drone operators to know when there's a change in the situation while they're flying—such as an emergency service helicopter barreling into their flight path.

So while the FAA's B4UFLY app and the collaborative program with AUVSI and the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) that spawned it are giving drone operators some very basic information, they're not exactly making the skies safe on their own. Drone safety, Marcus said, "starts with awareness for operators—giving them something that's easy to understand about where they can and can't fly safely, that's dynamic. It's similar to the B4UFLY concept, but we asked, 'How do we make that really useful?' That's how we started… we decided to look at how we go about building a safe and efficient operating environment for drones. The first element of that is awareness. And it's not just about how you display things on a map, but how you get that information into the hands of the operator."

There's an app (and an API) for that

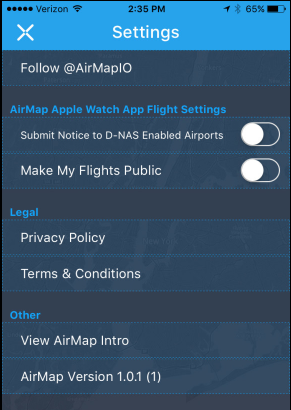

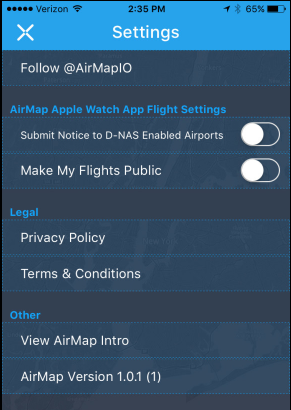

The AirMap iOS application is available on iPhones and also has an Apple Watch add-on. It allows a drone pilot to create a profile, including a "library" of aircraft and contact information, to be used to send notifications of flights. The app collects geolocation data, gives a color-coded message about flight restrictions, and offers the drone pilot the ability to notify airports within five miles of flight plans simply through a tap on the screen.

more images in gallery

Everything that's in AirMap's iOS app is also available in the AirMap application programming interface and software developer kit. The goal, Marcus said, is that "you don't need to open another app—you can see the information with the app you're already using to fly your drone. So if you attempt to take off within five miles of an airport, you get a pop-up message asking if you'd like to provide notice."

AirMap's app for iOS.

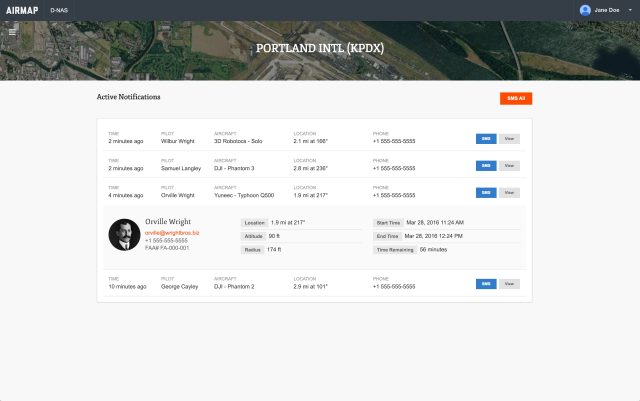

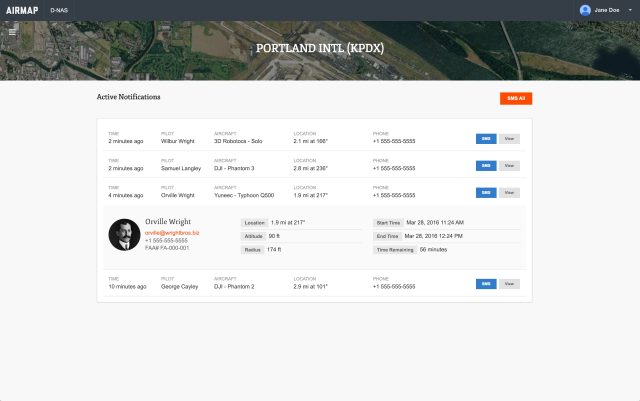

On the other end, airport operations centers can plug into the AirMap system, called the Digital Notice and Awareness System (D-NAS). These groups will use a "dashboard" application that allows them to see all of the notifications within their operating area. "We launched that program with the American Association of Airport Executives recently," Marcus said. In total, 75 airports signed up as of the first week of May—and more are in the pipeline. The airports already using the system include Los Angeles International, Houston George Bush Intercontinental, Denver International, and a host of regional and small airports. "We're also trying to figure out how to make the dashboard useful for heliports as well—more for the helicopter pilots who are landing than for a tower," Marcus added.

more images in gallery

The dashboard gives airport operators "a realtime map of where notices have been provided" by drone pilots, Marcus explained. "They can also, as the airport operator, click on any of those flights to get information on the type of drone and the altitude it's flying at, and [they] can send an SMS message to the operator from the dash." That SMS message can be manually typed in or automated.

Additionally, the dashboard allows airport managers to set geo-fence-based rules that can automatically set an area as more permissive of drone flights or explicitly exclude drones from flying in the area (such as the approach paths being used for landing aircraft). On the drone operator side, that means the SMS messages approving flying can be used as a handy way to show police that, yes, they have permission to be flying.

Within the next month, AirMap will add traffic alerts to the iOS app and the API. These alerts are based on aircraft transponder data and other sources, and they will warn drone operators of aircraft that are coming into the airspace they're using. For airports and helipads currently not enrolled in the service, AirMap pulls contact data (including phone numbers) from the FAA's database—ironically, something the FAA neglected to do with its own app.

While AirMap has partnered with specific drone manufacturers, the API is available to anyone building their own drone. The iOS application (which will be followed shortly by an Android app) is intended largely to demonstrate the features of the API—which includes map tiling and other geo-spatial data independent of what's built into iOS or Android, Marcus said. "The second reason is so that we can allow people who do not have a drone built by one of these manufacturers to also participate in the system—if you're building a drone in your garage or flying something rudimentary, maybe even without GPS—you can still participate with the digital notice."

In robots we trust

While the AirMap app addresses operations within line of sight, future drones flying autonomously will need a whole additional layer of communication to operate safely. In particular, these devices will need drone-to-drone communication to help "deconflict" any potential collisions in more crowded skies. Again, Kimchi outlined Amazon's proposal for how this would work—a system in which services like AirMap would be part of a larger "federated" traffic control system, providing both rules for general drone traffic flow and automated alerts and responses to potentially dangerous situations.

These sorts of federated services are something Internet service developers like Amazon are already familiar with. But such setups are currently far outside the FAA's comfort zone, and this would require a cultural change in how the aviation industry views automation.

Kimchi remarked on the irony of how the aviation industry currently uses autopilots to land aircraft in foggy conditions when pilots can't see the runway, yet they don't trust the systems in good weather when the risk is lower. "We already trust the automation in the worst possible conditions, why don’t we trust it the rest of the time?” he told the AUVSI conference crowd. So when drones can both sense and avoid hazards and share data amongst themselves about such hazards, organizations like AirMap and Amazon believe UAVs will be able to fly safely in public airspace—doing so in much greater numbers.