Today all that’s left of the ancient city of Semiyarka are a few low earthen mounds and some scattered artifacts, nearly hidden beneath the waving grasses of the Kazakh Steppe, a vast swath of grassland that stretches across northern Kazakhstan and into Russia. But recent surveys and excavations reveal that 3,500 years ago, this empty plain was a bustling city with a thriving metalworking industry, where nomadic herders and traders might have mingled with settled metalworkers and merchants.

Radivojevic and Lawrence stand on the site of Semiyarka.

Credit:

Peter J. Brown

Radivojevic and Lawrence stand on the site of Semiyarka.

Credit:

Peter J. Brown

Welcome to the City of Seven Ravines

University College of London archaeologist Miljana Radivojevic and her colleagues recently mapped the site with drones and geophysical surveys (like ground-penetrating radar, for example), tracing the layout of a 140-hectare city on the steppe in what’s now Kazakhstan.

The Bronze Age city once boasted rows of houses built on earthworks, a large central building, and a neighborhood of workshops where artisans smelted and cast bronze. From its windswept promontory, it held a commanding view of a narrow point in the Irtysh River valley, a strategic location that may have offered the city “control over movement along the river and valley bottom,” according to Radivojevic and her colleagues. That view inspired archaeologists’ name for the city: Semiyarka, or City of Seven Ravines.

Oldowan choppers dated to 1.7 million years ago, from Melka Kunture, Ethiopia.

Credit:

By Didier Descouens - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11291046

Oldowan choppers dated to 1.7 million years ago, from Melka Kunture, Ethiopia.

Credit:

By Didier Descouens - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11291046

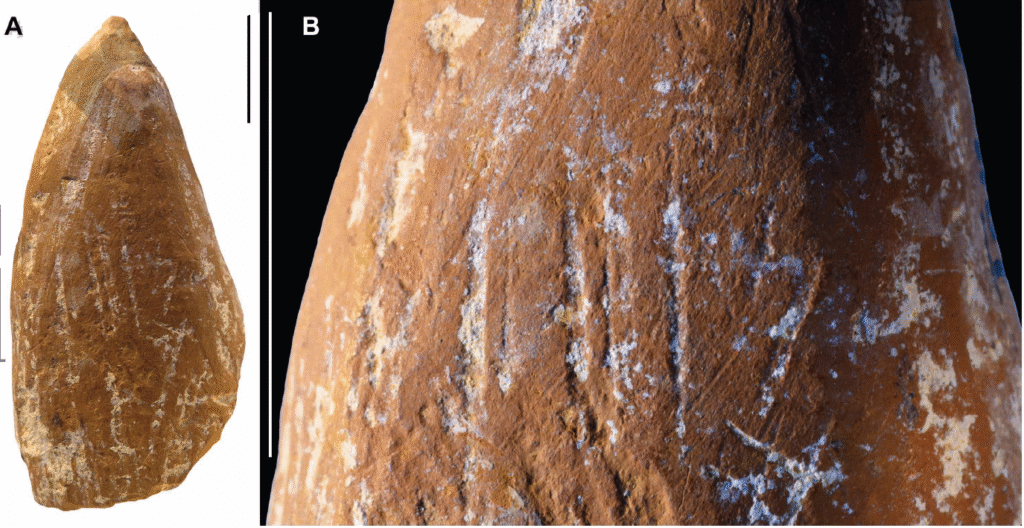

This piece of yellow ocher was used as a crayon and resharpened before finally being worn blunt and discarded.

Credit:

D'Errico et al. 2025

This piece of yellow ocher was used as a crayon and resharpened before finally being worn blunt and discarded.

Credit:

D'Errico et al. 2025

The skull of an early hominid.

Credit:

The skull of an early hominid.

Credit: