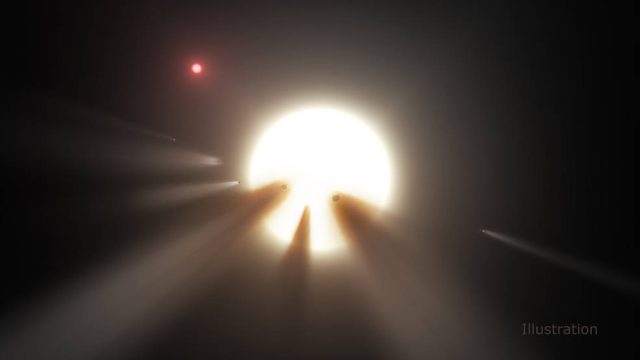

One of the earlier leading candidates to explain the odd behavior of this star. The new data suggest this explanation is unlikely.

For over a century, a star's bizarre behavior has been hiding in plain sight. Now, after unusual fluctuations in its light were spotted in the Kepler data, a researcher has gone back and looked at old photographic plates and found that its behavior has been unusual since some of the earliest images. The new findings make any mundane explanations for the star's erratic behavior even less likely.

"The star KIC8462852 (TYC 3162-665-1) is apparently a perfectly normal star." That's how a new paper from Louisiana State's Bradley Schaefer begins. It's an F-type star, which means it's a bit larger than the Sun, but is otherwise boring and stable. If you were to image it (as has happened many times over recent decades), it would look unremarkable.

It took the Kepler telescope to figure out that the star was anything but boring. Kepler was designed to stare at one patch of the sky and watch for signs of planets passing in front of their host stars. By chance, that patch of sky included KIC8462852. Its bizarre behavior—sudden dips in brightness of as much as 20 percent, lasting for seemingly random periods of time—wouldn't have been identified by the software that analyzes Kepler data.