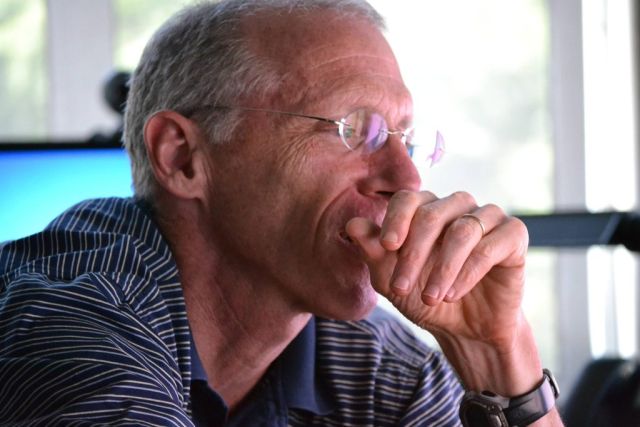

During hours of unrelenting cross-examination today, Andy Rubin, Google’s former Android chief, was on the stand in the Oracle v. Google trial defending how he built the mobile OS.

Rubin’s testimony began yesterday. He's another one of the star witnesses in this second courtroom showdown between the two software giants in which Oracle has said it will seek up to $9 billion in damages for Google's use of certain Java APIs in the Android operating system. Since an appeals court decided that APIs can be copyrighted, Google's only remaining defense in this case is that its use of those APIs constitutes "fair use."

After selling his earlier company, "Danger," Rubin said he founded Android in 2003. It was acquired by Google in 2005. Rubin stayed on as Google’s point man in charge of the company’s most ambitious project since search—creating an open source mobile operating system that could power smartphones around the world. It was a mission with incredible urgency, especially after Apple launched the iPhone to great fanfare in 2007.

Oracle attorney Annette Hurst questioned Rubin for more than four hours, asking Rubin about the timing of the Android launch, whether a license was needed, and his compensation.

Hurst's cross was the most aggressive questioning yet of a Google witness. As she asked questions, she paced back and forth in the small space between the lawyers' podium and the table at which Oracle's team of lawyers sat. Her style contrasted with that of Rubin, who has grown a beard and a Fu Manchu-style mustache since leaving Google. Rubin answered in a slow and quiet tone and never lost his cool, although he sometimes seemed exasperated.

"You were under incredible schedule pressure, weren't you?" Hurst asked early on in her questioning.

"Yes," Rubin said. "I wanted to win."

"And, you were under [Google founder] Larry Page?" she asked.

"I never felt any pressure from Larry," Rubin said. "That wasn't his management style."

Big rewards, big risks?

Rubin had a huge financial stake in Android's success, and Hurst zeroed in on it. When Android was acquired by Google, he held stock worth about $2.6 million, and members of his family had small amounts of stock as well.

Then she showed Rubin's contract with Google, detailing four "milestones" that would give him huge bonuses. The beginning milestone was when the first working smartphone was shipped within a certain time frame—worth $8 million to Rubin. The next milestones came when 5 million, 10 million, and 50 million phones were shipped, respectively; they would earn Rubin $10 million, $15 million, and $27 million, respectively.

Hurst: Wasn't all of that $60 million riding on you meeting that first milestone?

Rubin: It wasn’t just me, we had a team.

Hurst: Isn’t it true that all that $60M would be forfeited if you didn’t meet that first milestone?

Rubin: That’s what the contract stated. Whether it would have happened or not is another thing.

Hurst: So you don’t believe in honoring contracts, Mr. Rubin?

Rubin: I absolutely do believe in honoring contracts.

Rubin's team used three different terms to refer to early ideas about their phones. One was the "dream"—the dream phone they wanted to ship—and then there was the "sooner" version and the "later" version. After they saw the iPhone unveiled in 2007, they threw out the idea of shipping "sooner," presumably because it wouldn't have been any match for the Apple product.

Building up the core libraries, the heart of the programming in Android, was a huge task. Under Hurst's questions, Rubin said he did try to get libraries elsewhere, from IBM and others.

"I was constantly looking for ways to speed up the effort, and getting people to contribute to the open source project was part of that," he acknowledged.

"Didn't you testify on direct there was a 'clean room' implementation of the core libraries?" Hurst asked.

"A clean room means you don't copy stuff out of someone else's book, right, Mr. Rubin?" Hurst said, nearly shouting. She picked up a book of the Java language on Oracle's table.

"That depends," said Rubin. "There are books about open source software."

"So you don't even know if there's a clean room or not?" Hurst asked, throwing her arms up.

Google's lawyer objected. The judge sustained.

"A clean room has to be done without copying someone’s specifications, isn’t that true?" Hurst asked.

"It depends whether the specification is open or not," Rubin answered. "There are some specifications that don’t taint a clean room. For example, Apache Harmony, I didn't think that tainted anything."

"So you thought it was okay to take Sun's stuff if it was in Apache Harmony?" asked Hurst. (Sun created the Java language and APIs and was acquired by Oracle in 2010.)

Rubin remained stoic. That wasn't what he had said.

Looking for a cover-up

Finally, Hurst turned to an e-mail that has come up many times during both the earlier trial and this one. The 2010 e-mail, from engineer Tim Lindholm, informs Rubin that Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin asked him for "technical alternatives to Java."

"We've been over a bunch of these, and we think they all suck," Lindholm wrote. "We conclude that we need to negotiate a license for java under the terms we need."

Rubin acknowledged that he'd seen that e-mail.

"He didn't write, 'we don't need a license because of Jonathan Schwartz's blog,' did he?" shot Hurst. Google again objected to her question as argumentative and was sustained.

In another e-mail exchange, Rubin was asked about another company's plan to use Java.

"Wish them luck," Rubin wrote. "Java.lang.apis are copyrighted. and sun [sic] gets to say who they license the tck to," Rubin wrote.

Hurst pulled up another set of e-mail exchanges that had to do with a UK engineer who had been quoted in a 2007 Computerworld article about Android. The engineer said Google had its own APIs and "a better flavor of Java."

"PR Team—can you make sure that only authorized speakers speak to the press?" Rubin wrote after seeing the article. "This is really important, and a legal issue."

On re-direct, Rubin had the same explanation for avoiding the term Java that other Google witnesses had: the company didn't have a license to use the trademark, which required payment. He saw that separately from the copyright issue.

"The basis for your belief that APIs were not copyrightable was folklore and industry stories, isn’t that true?" Hurst asked, closing her cross-examination after more than four hours.

"No," Rubin started. "I think—"

Yes or no, Mr Rubin," Hurst said. "Folklore and industry stories?

"No," said Rubin.

Rubin was off the stand in the afternoon. US District Judge William Alsup warned both sides they've each been allotted 900 minutes of time in front of the jury, and they were burning through it, with Google having used 275 minutes and Oracle having used 380 in its cross-examinations.

Argumentative questioning like Hurst's—objections to her style had been sustained repeatedly—wasted those minutes, he noted. "I do not plan to enlarge the time," said Alsup.

Testimony will resume tomorrow morning.