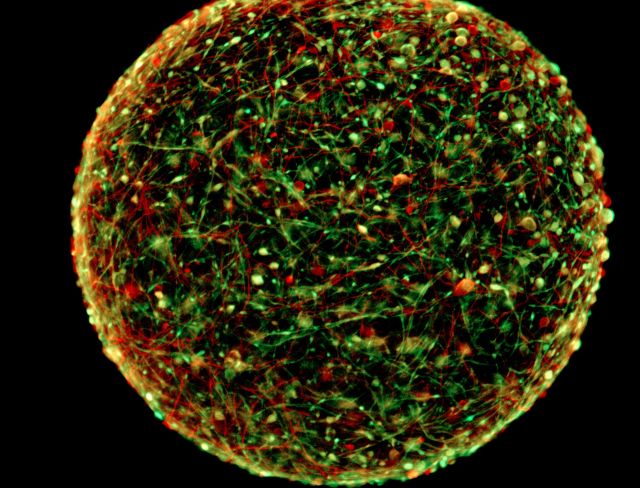

(credit: Lisa Roe)

What happens in the testes, stays in the testes. At least, that’s according to frustrated researchers who have spent years trying to understand and recreate the process that generates sperm. But now, in a satisfying data release, a group of Chinese researchers report that they’ve finally cracked that nut.

In the study, published Thursday in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers describe using mouse stem cells to generate rudimentary sperm that was used to fertilize eggs and produce healthy mouse pups. If true, the study could pave the way for the development of human sperm in lab dishes for fertility treatments.

“The results are super-exciting and important,” Jacob Hanna, a stem cell scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, told Nature. However, several other researchers said they were skeptical of the data and anxious to see the results repeated in other researchers’ hands. “You have to be very cautious about the implications of this paper,” Mitinori Saitou of Kyoto University said.