Famous quarantine in 1665-6 provided perfect conditions to study transmission.

Without a doubt, the bubonic plague has been one of the deadliest and most devastating infectious diseases in all of human history. The bacterial infection—caused by Yersinia pestis—has sparked dozens of outbreaks and three massive pandemics, killing hundreds of millions of people. The Justinian Plague from 541 to 767 is estimated to have killed up to 50 percent of the population at the time and spurred the demise of the Roman Empire. Likewise, the fourteenth century Black Death, which circumnavigated Europe in just a few years, ended up slaughtering as much as 60 percent of the continent’s population.

Yet, despite the indelible mark the dark disease has left on humanity, researchers still aren’t certain how exactly Yersinia sweeps through cities and countries. The highly infectious disease has historically been linked to rodents, in which the bacteria can fester, and rat fleas, which take in and then vomit out the bacteria in subsequent bites. Thus, booming vermin populations have long been assumed to spark and sustain outbreaks. But a fresh analysis of a tiny village in England—made famous for its handling of a plague outbreak from 1665 to 1666—stands to challenge the view.

The Derbyshire village of Eyam, estimated to have a population of around 700 at the time of the outbreak, took the remarkable step of imposing a quarantine on itself—a move almost unheard of at the time. While the villagers aimed to spare neighboring parishes—which they did—the quarantine and the villagers’ detailed death records also provided a perfect opportunity for studying plague transmission dynamics.

In a new analysis of the outbreak, researchers estimate that rodent-to-human transmission accounted for only a quarter of all infections, while human-to-human transmission made up the rest. The finding, published Wednesday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, adds fuel to a hot debate among academics about how plague spreads. And, more importantly, it has the potential to inform public health responses to modern-day plague outbreaks, which still occur around the world, particularly in Africa and South America (albeit on much smaller scales than historical outbreaks).

“This debate is not just of historical importance but also of contemporary relevance to help deal with this neglected tropical disease, which could someday become a worldwide public health priority again,” the study authors, Lilith Whittles and Xavier Didelot of Imperial College London, concluded.

They arrived at the point by first digging into historic population and death records of Eyam—now known as “plague village.” The researchers looked at factors such as age, wealth, household structure, and gender of the 257 people who died of plague. The deaths, which began after the delivery of flea-infested cloth from London, lasted from September 1665 to October 1666.

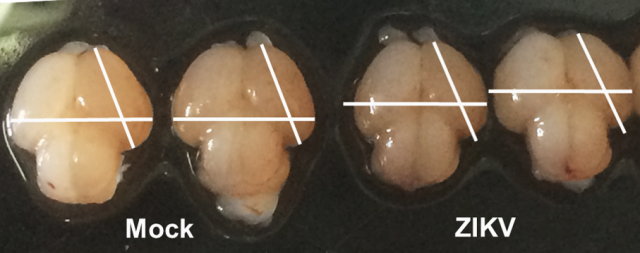

Next, the researchers used a stochastic compartmental model and Bayesian analytical methods to recreate the pattern of deaths and trajectory of the outbreak revealed by the records. The model included rodent-to-human transmission and human-to-human transmission, which was estimated to occur within a fixed window of 11 days between exposure, infection, and death. (While there were oral reports that three villagers recovered from the plague, those weren’t recorded in documents so the researchers tossed them out of their main analysis. However, when they did try including them, it didn’t alter their overall findings.)

The researchers found that human-to-human transmission accounted for 75 percent of all infections, with age, wealth, and household structure playing big roles in who got sick. Kids and family members of victims were the groups most affected by the plague. The village’s wealthy were less likely to get the plague, possibly due to less contact with general village folk and vermin.

Plague is known to transmit from person-to-person in bodily fluids and aerosols—formed by coughing, which is generally associated with pneumonic plague. But the researchers speculate that such transmission routes were unlikely, given the historical records of people’s symptoms, which rarely included pneumonia. Instead, the researchers hypothesize that lice and human fleas may have been a main bridge by which Yersinia got around. And the finding makes sense with the spread among lower-class kids, who could easily share head lice while playing.

Though the study looked at just one, isolated, historic outbreak, the authors argue that the “results feed into the long ongoing debate about the role of interhuman transmission through human ectoparasites.”

Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2016. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0618 (About DOIs).