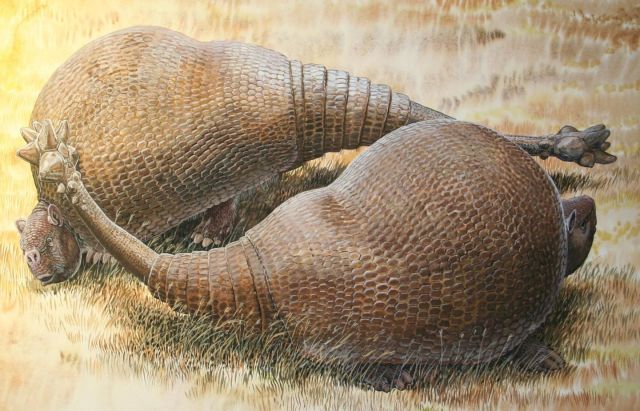

Two giant Glyptodonts, covered in solid shields of armor, smash each other's little faces with spiked club tails. Just another day in the Pleistocene. (credit: Peter Schouten)

If you missed the Pleistocene in the Americas, you never got to see all the fantastic megafauna we once had here: mastodons, sabre tooth cats, giant sloths, hippo-rhino-looking Toxodons...and 3,000-pound armored beasts called Glyptodonts. Now a new DNA analysis reveals that Glyptodonts are extinct cousins of present-day armadillos. Except these creatures were the size of small cars and could smash you with their spiky, clubbed tails.

At least, some species of Glyptodont could smash you—others did not have clubbed tails, though all of them would have looked to our modern eyes like freakishly outsized armadillos. What's interesting is that these creatures evolved to their massive sizes in a relatively short time. The researchers, who published their findings in Current Biology, say the last common ancestor of Glyptodonts and today's armadillos was a 175-pound animal who toddled around South America about 35 million years ago.

Since that evolutionary divergence, some Glyptodonts, such as the massive Doedicurus (the one with the clubbed tail), grew to 1.5 tons in weight.